Executive Summary

The Italy-Albania Migration Protocol, ratified in early 2024, marks a significant step in the EU’s strategy to address migration by shifting control to non-EU territories. This agreement allows Italy to operate two migrant processing centers on Albanian soil, specifically aimed at intercepting and detaining migrants found in international waters before they reach Europe’s borders.

Given its nature, the Protocol has ignited significant controversy. Even though the Albanian Constitutional Court upheld the agreement’s constitutionality, unresolved issues persist, particularly around dual jurisdiction, transparency, and the protection of fundamental rights. With increasing concerns over the adequacy of legal protections for detained migrants, the Protocol’s compliance with EU standards remains an open question.

The main points of consideration of this policy study include defining jurisdictional responsibilities with greater precision, strengthening legal safeguards and oversight processes, and ensuring active involvement from EU bodies and civil society organizations in ongoing monitoring.

Foreword

This report offers a deep dive in the Italy-Albania Protocol and its constitutional, legal and human rights implications from the Albanian perspective of Albania. We feel this is a necessary complement to the analyses offered from the perspective of Italian and European Union Law.

There have been several developments that have delayed the Protocol’s implementation in recent weeks. In a crucial decision of 18 October 2024, a civil court in Rome ruled that twelve asylum seekers originally sent to the Gjadër camp to be submitted to an accelerated procedure had to be returned to Italy, citing concerns over their countries of origin, which the court determined could not be considered safe. This ruling reflects a recent European Court of Justice decision, stating that a third country cannot be deemed a safe country of origin unless all regions of that country are free from risk of persecution or inhumane treatment. In response, the Italian administration elevated the designation of “safe countries” from a ministerial decree to a formal act of law. This adjustment aims to fortify the government’s stance and potentially limit further judicial intervention. Additionally, on November 6, 2024, the Italian government dispatched a second, smaller group of migrants to Albania as a controlled test to navigate legal and operational challenges.

Despite these challenges and setbacks, the Protocol, its operational modalities and the effort to secure the rights of migrants and asylum seekers will continue to occupy the minds of scholars and policy-makers alike, irrespective of whether the Protocol meets its stated goals. The reason is that the Italy-Albania Protocol is another iteration of the turn towards externalization, a persisting leitmotif in European migration management governance.

Dr Markos Karavias

Director

MedMA

Overview

Under the Italy–Albania “Migration Protocol” (hereafter Protocol) of November 3, 2023, ratified by the Albanian Parliament on February 22, 2024, Italy funded the construction of two Centers of Permanence and Repatriation (CPR) (hereafter Migration Centers) on Albanian state-owned property—the northern port of Shëngjin and the former military airport of Gjadër (Annex 1)—that were temporarily allocated to the Italian government. These locations will serve as facilities for the identification and accommodation of irregular migrants intercepted in international waters while attempting to reach Italian soil 1This only applies to male migrants. It excludes minors, pregnant women, and other vulnerable individuals..

After their planned inauguration in May 2024 was delayed,2The initial plan for the full operation of the centers was set for May 2024. Euronews, May 20th, 2024 the two migration centers established under the Protocol commenced their operation on October 16. The Italian interior ministry confirmed on October 14 that 16 men—10 Bangladeshis and six Egyptians who had reportedly departed from Libya and were rescued by the Italian coastguard in international waters the day before—disembarked at Shëngjin port and were subsequently transferred to Gjadër.

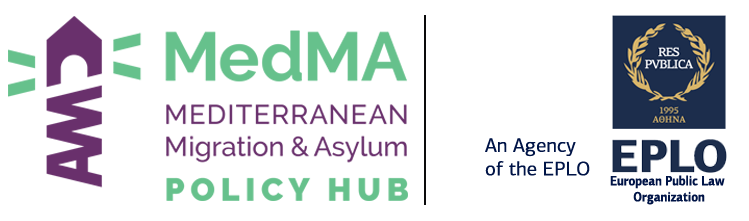

A migrant center is seen from above in the port of Shengjin, northwest Albania. Photo by Ilir Tsouko, 2024

Although these areas remain part of Albania’s sovereign territory, they will be temporarily used exclusively by Italian authorities, as outlined in Articles 3 and 13 of the Protocol.3The Albanian side reserves the right to renew or not renew the Protocol at the end of its five-year term, as well as to terminate or denounce it, in accordance with the explicit provisions outlined in Article 13 of the Protocol. Upon arrival at these centers, which operate under Italian jurisdiction, Italian officials will oversee the disembarkation and identification processes, establishing an initial reception and screening center. It is estimated that between 3,000 and 36,000 individuals could be processed annually. Asylum seekers and migrants will remain in Albania throughout the application process and possibly until their repatriation. The Albanian police will provide security and external surveillance for these facilities.4The personnel involved will operate partly in Italy and partly in Albania. While the agreement allows for Italian personnel to be dispatched to Albania to “ensure the execution of the activities outlined in the Protocol” (Article 1 Protocol), the ratifying law specifies that only judicial police, prison police, and a special maritime, air, and border health office will be stationed in the designated areas. Furthermore, the Protocol includes several provisions stipulating that all expenses associated with this initiative will be borne by the Italian side, which will also cover any costs incurred by the Albanian side as a result of the Protocol. On August 14, 2024, the UNHCR announced5UNHCR Italia, August 14, 2024 that, while not involved in the negotiations, it will play a monitoring role for an initial three-month period, after which it will provide its recommendations to the Italian government.6The Agency’s stance has drawn criticism for potentially legitimizing the Protocol and promoting the externalization of asylum procedures by other countries in the Global North. For more information, see Il Manifesto, August 18, 2024

According to the Report on the Law “For the ratification of the Protocol, between the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Albania and the Government of the Italian Republic, for strengthening cooperation in the field of migration” (hereafter Law) the Protocol for ratification aims to enhance cooperation between the Albanian government and Italy, which is crucial for Albania’s European Union aspirations.7Report on the Draft Law, November 17, 2023, [in Albanian]. While initiated by Italy, the Protocol is significant for Albania, as it addresses the management of irregular migration flows, an issue of mutual interest for the region. Furthermore, by engaging in this Protocol, Albania seeks to reshape its image from a source of illegal migration to a proactive participant in regional stability, promoting regular migration in line with international standards. According to the rationale of this Law, this cooperation not only aids Italy but also contributes to the broader European Union effort to manage migration challenges that have become increasingly pressing in recent decades. Additionally, Albania’s active involvement is seen as a testament to its role as a reliable ally to the EU, highlighting its unwavering commitment to European integration. While it is acknowledged that the Protocol allows specific Italian authorities to exercise certain competencies within Albania, it only mirrors other international agreements where countries grant rights to foreign bodies to manage specific matters on their territory.8A notable example is the agreement between Albania and the EU, allowing the European Border and Coast Guard Agency to operate in Albania, thereby enhancing its capabilities to combat illegal migration and transnational crime. Overall, this initiative signifies Albania’s strategic alignment with EU objectives while addressing regional migration concerns effectively.

Reactions to the Protocol

The Protocol has sparked considerable controversy within Italian, Albanian, and broader EU legal and political spheres. As the first agreement of its kind involving an EU candidate country, it is fraught with complexities regarding its implementation and alignment with both national and EU law.9Mazelliu, A. and Methasani, E., Questione Giustizia (January 2024). Although the Protocol is part of a broader trend of outsourcing migration control, it is unique in that it involves Albania, a country seeking EU membership.

The Protocol is bound to attract scrutiny over its constitutionality and compliance with EU standards, especially in light of problematic precedents set by similar agreements in the UK, Denmark and Australia.10Even though the Italy–Albania Protocol is comparable to the UK’s controversial deal with Rwanda, it differs in that Italy will manage the centers directly, whereas the UK was supposed to send migrants to centers managed by Rwanda. More importantly, Albania is protected by the European Convention on Human Rights, which means the migrants there are subject to different legal protection. In this respect, international human rights organizations have sharply criticized the deal, with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) condemning it, stating that it “strikes a further blow to the principle of EU solidarity,”11IRC Press release, July 24, 2024 while Doctors Without Borders (MSF) have argued that it sets a dangerous precedent for asylum management by adding that “the lack of access to Italian soil, the extraterritorial management of asylum applications, the application of accelerated border procedures and the detention of people in a third country represent a new attack on the right to asylum, as it is understood today.”.12CNN, November 7, 2023 Similarly, an Open Letter signed by 29 Albanian human rights organizations called for Albania’s withdrawal from the Protocol citing the absence of legal provisions that stipulate the stay period and the actual duration of asylum request reviews (six months to a year) or appeals handled by Italian authorities. The letter highlights that Italy’s records of delays in examining the asylum requests may unfairly restrict the freedom of movement for asylum seekers, violating the international principle of “non-refoulement” with potential legal consequences for the Albanian State.13Albanian Helsinki Committee, March 12, 2024

On the Italian national plan, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni views the Protocol as a potential model for EU–non-EU cooperation in managing migration flows, describing it as a significant breakthrough in addressing one of Europe’s pressing challenges.14Euronews, November 14, 2023 Despite criticism related to similar deals with Libya, where severe human rights abuses have been reported,15Human Rights Watch, July 21, 2023 Meloni defends the Protocol as a forward-looking example of European spirit. Furthermore, the Italian premier hailed the deal as a “European agreement” and an “innovative solution” aimed at curbing the rise in crossings over the Mediterranean Sea from North Africa.16CNN, November 7, 2023/mfn] The Italian opposition has condemned the plan as a form of deportation reminiscent of controversial extrajudicial detention camps.16RFI, January 30, 2024 Riccardo Magi, the leader of the opposition party Radicali Italiani, defined the migration centers as “Guantanamo made in Italy.”17Balkan Insight, November 8, 2023 Similarly, the Director of Amnesty International’s European Institutions Office said that “this cruel experiment is a stain on the Italian government.”18Amnesty International, July 31, 2024 In an address to Italian Senate, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that “transfers to Albania to conduct asylum and return procedures raise important human rights issues, particularly freedom from arbitrary detention; adequate asylum application procedures, including screening and identification; and living conditions.”19Reuters, January 25, 2024

At the EU level, the agreement is seen as part of a broader effort to manage irregular migration more effectively. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has endorsed the agreement as an innovative approach to fair responsibility sharing with third countries by praising the initiative as “out-of-the-box thinking based on fair sharing of responsibilities with third countries.”20AP News However, other EU institutions have taken a more ambiguous stance, with the EU Commissioner for Home Affairs stating on November 15, 2023, that “the preliminary assessment by our legal service is that this is not violating the EU law, it’s outside the EU law.”21Euronews, November 15, 2023 In May 2024, 15 EU member states referred to the Protocol as a potential model for partially outsourcing the EU’s migration and asylum policy. Prime Minister Rama emphasized that the Italy–Albania Protocol is a unique agreement and that his government will not seek similar deals with other countries. This assertion came in response to UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s expressed interest in the Protocol, which allows for the transfer of individuals intercepted in Italian waters to reception centers in Albania. During a session of the European Parliament, Rama remarked, “This is an exclusive agreement with Italy because we love everyone, but with Italy, we have unconditional love.”22Euronews, September 19, 2024

Beyond the EU, the Council of Europe has raised concerns about potential human rights violations and legal uncertainties, which could set a troubling precedent for future migration agreements. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern by emphasizing that “the lack of legal certainty [inherent to the Protocol] will likely undermine crucial human rights safeguards and accountability for violations, resulting in differential treatment between those whose asylum applications will be examined in Albania and those for whom this will happen in Italy.”23Commissioner for Human Rights, November 13, 2023 Hence, its implementation might violate access to justice, effective remedies, and access to legal aid because of the automatic detention of migrants and asylum seekers in an extra-territorial regime.24IOM, March 23, 2022

Migration Center in Gjadër, Photo by Ilir Tsouko, 2024

Legal Challenges to the Protocol

In Italy, concerns have been raised that the Protocol may violate the Italian Constitution, particularly Article 80, which governs the ratification of international treaties. Similarly, in Albania, the Protocol has been challenged for potentially breaching constitutional provisions and ECHR standards.

On January 29, 2024, Albania’s Constitutional Court ruled that the Migration Protocol with Italy is constitutional after reviewing the physical and legal implications for Albanian sovereignty. First, the Court determined that the Protocol does not alter Albania’s territorial borders or integrity, indicating that there are no changes to the country’s physical territory. Second, it found that both Albanian and Italian laws will apply in the two areas covered by the Protocol.25Constitutional Court, Decision V-2/24, January 21, 2024, [in Albanian]. Available here. More specifically, the Court concluded that the Protocol does not affect Albania’s territorial jurisdiction concerning the Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), or ratified international agreements. Consequently, the Albanian State will continue to exercise its jurisdiction, even while the Migration Protocol is in effect. Additionally, the Protocol outlines the temporary transfer of two areas from the Albanian State to Italian State authorities, who will exercise jurisdiction over matters such as healthcare services (Article 4), internal order and security within the zones, food services, and any other necessary provisions (Article 6), as well as the legal process for reviewing asylum requests (Article 9). Meanwhile, Albanian authorities will retain jurisdiction over aspects such as healthcare services (Article 4), external order and security (Article 6), facilitating assistance for asylum seekers, and services related to the transfer of bodies in case of death (Article 9). However, the Court also acknowledged the unique nature of the Migration Protocol, which permits Italian authorities to exercise jurisdiction alongside Albanian authorities, specifically concerning asylum-related matters within designated areas of Albanian territory.26Despite the Albanian Constitutional Court’s final decision on January 29, 2024, affirming the agreement’s constitutionality, it remains under scrutiny as it moves toward implementation.

Flags in the Reception Center at the port of Shengjin, Photo by Ilir Tsouko, 2024

Regarding EU standards and human rights concerns, the Protocol’s adherence to EU acquis standards may be questioned. The 2016 EU–Turkey agreement can be considered a more structured model compared to the Italian–Albanian Protocol, as it was based on pre-existing legal arrangements, such as the 2014 EU–Turkey readmission Protocol, and it allowed returns only for migrants (from Greece) not seeking asylum or those with inadmissible claims. In contrast, the Italian–Albanian Protocol lacks clarity on compliance with EU asylum procedures and human rights protections, potentially impacting access to protection and legal remedies as outlined by the ECHR.27Mazelliu, A. and Methasani, E. Questione Giustizia (January 2024).

In a broader context, the Protocol may be viewed as a paradigm reflecting new political trends in the EU, triggering concerns regarding the:

- Externalization of Migration, with Italy’s outsourcing of asylum processing to manage migration outside its borders, while Albania viewing it as an opportunity to reshape its image from a source of illegal migration to a proactive participant in regional stability.

- EU Enlargement, with the Protocol underscoring Italy’s strategic role in Albania, reflecting a neo-colonial approach. It seems that Italy seeks to bolster, or revive, its colonial influence in Albania, leveraging this partnership to offset concerns about Albania’s democratic standards deficit and its EU accession prospect.

- Human Rights, with the Protocol raising significant concerns regarding the right to asylum by undermining established protections through extraterritorial management of asylum processes. Despite the Albanian Constitutional Court’s ruling on the agreement’s constitutionality, unresolved issues remain, including the applicable jurisdiction, the standing of Albanian courts, and the efficiency of processing asylum claims.

This policy study aims to address these concerns through an analysis of current developments and legal and political opinions. It seeks to highlight the ambitious externalization efforts from the Albanian side and examines the constitutional risk management prompted by the Italian–Albanian Protocol along with its implications for human rights protection.

Constitutional and Legal Risks

In November 2023, the Italian and Albanian Prime Ministers announced the signature of the “Migration Protocol” in a surprise press conference. The procedure of negotiations and drafting of the Protocol has been carried out in relative secrecy, and the public opinion was notified only at the moment of signature. Despite the fact that this “silent” procedure is not illegal, per se, it gives grounds to fears of a lack of transparency. In issues regarding the treatment of humans and their basic rights, concepts of secrecy should normally be avoided based on the importance that human rights have both in international and domestic legislation and their treatment as jus cogens, which is a concept enshrined in Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

The location of the camps is scheduled to be on two old military bases in Lezha district, which form part of the property of the Albanian State. According to the Protocol, such locations shall be managed by the Italian authorities, Italian and EU law shall apply within the locations, and disagreements between migrants and Italian authorities shall be settled exclusively by Italian jurisdiction (Article 4/2).28The Protocol between the Government of the Italian Republic and the Council of Ministers of the Albanian Republic was retrieved from https://bit.ly/3UJtaps

The Protocol gives rise to a series of questions as per its negotiation history, its content vis-à-vis the Albanian legislation, its alignment with the obligations of the Albanian State as a Party to the European Convention on Human Rights, the 1951 Refugee Convention, and other human rights instruments.

Taking a sidestep from the legal aspects of the Protocol, one should note that the Protocol was presented, politically debated and justified on the basis of the so-called “debt” that Albania has toward Italy for hosting and integrating hundreds of thousands of Albanians at the end of the communist regime and the economic collapse of the country.29BalkanWeb, (2023).

Setting emotional and historical connections aside, this paper presents an overview of key administrative and human rights concerns related to the applicability of the Protocol, its outcomes and implications, inter alia, under the prism of the decision of the Albanian Constitutional Court, which on a 5 to 4 decision, upholds the constitutionality of the Protocol.30Constitutional Court of Albania, Decision V-2/24, January 29, 2024.

1.Territorial applicability and integrity: According to the Albanian Constitution (Article 116) ratified international agreements, the laws and normative acts are valid for the entirety of the Albanian territory, which, in principle, also includes the validity within the territory of public institutions’ activity and competencies.31Constitution of Albania, retrieved from here.

According to Decision Nr 2, dt. 29/01/2024 of the Constitutional Court, the Protocol establishes double jurisdiction applicability, which gives the Italian authorities the right to apply their jurisdiction in public law terms in the territory of Albania by limiting or excluding, in time and space, the applicability of Albanian law.

Furthermore, the Protocol provides concepts of sovereignty in Articles 4 et seq., which are applied by both parties at the same time and in the same place, such as the usufruct of immovable property belonging to the Albanian State. Therefore, in taking into consideration the concept of state sovereignty (see below), those actions will result in limiting Albanian legal jurisdiction and Albanian public authority jurisdiction. Those provisions have been defined by the concept of sovereignty, inter alia, as: “A state’s sovereignty is based on the exclusive power that it exercises over its territory and its nationals. In international law, states themselves (i.e., governments) write the rules that they will be required to follow.”32Hehir, J. Bryan. “Military Intervention and National Sovereignty: Recasting the Relationship.” In Hard Choices: Moral Dilemmas in Humanitarian Intervention, edited by Jonathan Moore, 29–54. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998.Therefore, the Protocol will inevitably limit the concept of Albanian State sovereignty.

It is evident that the Albanian State and/or government have decided to refrain from such applicability of rights to the two aforementioned areas where the camps will be deployed.

In this regard, the Protocol is an act of international law concerning territory and, as such, it has to fall under the stipulations of Article 121/ 1 of the Albanian Constitution, and therefore, a direct power of attorney should be given by the President of the Republic to the negotiating team and signatory authority.

Article 121:

The ratification and denunciation of international agreements by the Republic of Albania is done by law if they have to do with:

a) territory, peace, alliances, political and military issues,

b) freedoms, human rights and obligations of citizens as are provided in the Constitution,

c) membership of the Republic of Albania in international organizations,

d) the undertaking of financial obligations by the Republic of Albania,

e) the approval, amendment, supplementing or repeal of laws.

Apparently, such a provision has not been applied, and the Court has created a different approach from a similar case of signing and ratifying an international agreement based on the institution of sovereignty, such as the case of the agreement between Albania and Greece on the delimitation of the sea zones.33Constitutional Court, Decision Nr: 15, April 15, 2010.

2. Human Rights issues: Unlike what the Constitutional Court has claimed, this is an international agreement dealing with human rights.34Constitutional Court of Albania, Decision Nr. 2, dated 29.01.2024 (V-2/24), point 55, p. 25. The Protocol is limited in providing tools and remedies for such protection. With the exception of Articles 6/7 “The competent authorities of the Italian side will bear any expenses necessary for the accommodation and treatment of the subjects who will be accommodated in the structures mentioned in Annex 1, including food, health care (including cases where the assistance of the Albanian authorities is required for this) and any other service that will be deemed necessary by the Italian party, taking care that this treatment respects basic human rights and freedoms according to international law” that mentions the engagement of the Italian party to respect human rights and freedoms, there is no direct reference to any effective remedy and practical access to them.Therefore, the limitation of the applicability of Albanian legislation on the said premises shall limit the applicability of constitutional and international remedies concerning human rights.

From the other side the application of Italian legislation, jurisdiction and procedure represents serious difficulties regarding the right of access to justice and fair trial as they are enshrined in Article 6 of the ECHR.

Such difficulties include but are not limited to:

a. Distance: The applicant is physically in Albania and the courts are in Italy. Therefore, access shall by default be limited, and the Protocol has no provision of such supposed movements of the asylum seekers in order to follow their cases.

b. Costs: Distance is also connected to the concept of cost. Any legal assistance provided to those in camps will include added travel costs, independently who covers them.

c. Uncertainty of jurisdiction: According to the aforementioned decision of the Constitutional Court, both jurisdictions shall be applied on the territory of the camp(s). Article 9, paragraph 2, explicitly states: “To ensure the right of defense, the Parties allow the access to the facilities of lawyers, their assistants, as well as to international organizations and European agencies which provide advice and assistance to people seeking international protection, within the limits of the applicable Italian, Albanian and European law.”

Despite that at first glance this provision looks like it ensures a wide prism of protection, on the contrary, it creates discordance and confusion. Questions arise such as:

– What kind of legal assistance will be given, and on which legislation will it be based?

– Which procedure will be followed?

On the same topic, it is also important to note that, despite the bona fide concept mentioned in Article 26 of the Vienna Convention of the Law of Treaties, which should guide interstate relations, since the camps are in Albanian territory, the non-applicability and/or limitation of applicability of Albanian material and procedural law limits the legal and constitutional guaranties offered by the Constitution to all Albanian or foreign citizens but also to other persons without citizenship.

3. Obsolete legislation reference: The Protocol finds legal support in Article 19 of the Treaty of Good Friendship between Italy and Albania (1995), which refers to the mutual engagement of controlling migratory movements. The reference to this framework Protocol is ill-founded and out of scope; Article 19 refers to another time and problem. Its aim was to create a legal obstacle and deter the waves of illegal Albanian migrants who, at the time, were crossing the Adriatic in massive numbers and became a serious problem. The article provides specifically that: “The Contracting Parties agree to attach primary importance to close and energetic cooperation between countries to regulate, in accordance with the legislation in force, migratory movements (paragraph one). They recognize the need to control the migratory flow through the development of cooperation between the competent bodies of the Republic of Albania and the Italian Republic and the conclusion of an organic Protocol that also regulates the admission of citizens of both countries to the seasonal labor market, in accordance with the legislation in force (second paragraph). In order to achieve such objectives, a joint working group has been set up for migration problems (third paragraph).”35Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation between Italy and Albania, 1995, retrieved from here.

Therefore, applying an old treaty, whose letter and spirit meant something totally different in an attempt to justify today’s Protocols, brings an unsafe legal environment and severe vulnerability due to inconsistent facts, events and interests.

4. Acting ultra vires: The Constitutional Court on the aforementioned decision (point 64) notes that “the requests of the migrants of this Protocol, who will be accommodated in the territory of the Albanian State will be examined by the authorities of the Italian State, according to the legislation of the latter. This means that the Italian State, which during the implementation of Protocol on Migration will exercise its jurisdiction, is obliged to apply international norms for asylum seekers, refugees and human rights, which include the Geneva Convention and the ECHR, according to the principle of extraterritoriality.”36See above, Decision Nr 2, dated 29.01.2024, point 59.

What distinguishes this paragraph (and others similar to it) is the attempt of the Albanian Constitutional Court to demand specific action by the Italian State and authorities. Such demands are not only clear ultra vires but are also not realistically and practically applicable.

The Albanian Constitutional Court cannot extend its binding decision on issues involving Italian sovereignty and jurisdiction. Neither can predict or suppose that the Italian authorities shall always respect and perpetuate any breach of the basic human rights norms as they are foreseen by the Italian, EU and/or ECHR requirements and provisions. Therefore, such justification finds no sound legal logic, and its form of applicability is a grey area of overlapping jurisdictions.

5. Issues of Italian legislation: The Protocol provides for a period of 28 days from the moment of arrival to the final decision regarding asylum status.37See above Decision Nr 2, dated 29.01.2024, point 57. According to human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, this provision is highly problematic, since: a) automatic detention is inherently arbitrary and therefore illegal; b) the timeframe is unrealistic, since, combined with recent changes to the Italian law, the agreement could lead to people being detained continuously for more than 18 months; c) accessing legal aid and legal representation in Italy to challenge the legality of one’s detention from Albania would inevitably be very difficult, while people who disembarked in Albania will also face serious challenges in accessing asylum and effective remedies for human rights violations; and d) vulnerable people, such as children, pregnant women and survivors of trafficking and torture, will have to endure long and unnecessary transfers by sea and, due to shortcomings in screening procedures, they may be exposed to further harm.38Amnesty International,(2024)

6. Civil Law implications: According to the Protocol (Articles 4 and 5), the building of the structures shall be exclusively subject to Italian law, and such buildings do not need standard building permissions according to Albanian legislation. Therefore, local authorities have no jurisdiction over them or the related documentation, quality, safety measures, etc. It is therefore evident that the duality of jurisdictions as mentioned above finds no effective applicability in practice by creating thereof a serious legal gap.

Points of Consideration

The Memorandum between Italy and Albania on the sheltering of asylum seekers on Albanian soil has created a series of inquiries and insecurities regarding the due protection of their human rights and their access to justice. Despite a debatable decision made by the Albanian Constitutional Court on the constitutionality of the aforementioned agreement, there are still important concerns, especially regarding the type of jurisdiction to be applied, the locus standi on the Albanian courts, as well as on the time and efficiency of addressing their demands. The sheltering of such asylum seekers is today, and shall be even more tomorrow, one of the most important humanitarian and legal challenges of Albanian, Italian and EU legislation.

Even though the implementation of the Protocol has recently commenced, some general considerations can be drawn at this stage:

- Despite the immense pressure of the migratory waves and the difficult political reality this creates within EU governments, protection of fundamental rights and upholding of the EU acquis can never be considered an issue of secondary importance. Expedited administrative processes must entail fast and strong procedural guarantees.

- All legal remedies should be available and approachable; in this case, this involves the use of both Italian and Albanian court systems (mainly due to the duality of jurisdiction sanctioned by the decision of the Constitutional Court). The right to a fair trial should be secured from both sides of the Adriatic.

- Effective control needs to be applied by all legal actors of the civil society, the Ombudsman (in both Albania and Italy), since this is the first time such a Protocol is applied and, as we tried to demonstrate, all parties are navigating uncharted waters. The fact that the Albanian Ombudsman was involved from the very beginning of the case and became a party in the trial in front of the Constitutional Court is a step in the right direction.